| August 3, 2001 |

Toronto, Ontario

|

Dimitri

Messinis, The Associated Press

Whites

of Eurasian ancestry, such as pole vaulter Sergei Bubka of the

Ukraine, have stronger upper bodies.

|

Jerry

Lampen, Reuters

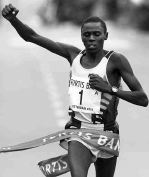

North

and East Africans, such as Kenyan marathoner Josephat Kiprono,

were born with a biochemical package for endurance activities.

|

Peter

J. Thompson, Thompson Sports Images

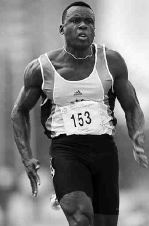

West

Africans, such as 100-metre specialist Bruny Surin, have a more

muscled physique and smaller lung capacity.

|

When the male marathoners open the world track and field championships tonight in Edmonton, expectations for Canada will be at an all-time low. Top Canadian Bruce Deacon, of Victoria, will be lucky to lag two miles behind the winner. Native-born Americans and Brits are not expected to do much better.

The favourite, Moroccan-born Khalid Khannouchi, faces a tough challenge from an elite field crowded with North and East Africans. Josephat Kiprono, the only marathoner to break 2:07 twice is one of two Kenyan challengers.

So what has befallen the great Northern European-North American distance-running tradition, which dominated for so many years?

Here's a startling prediction: No homegrown North American, white or black, may ever set another world record in a distance race. The world rankings, which combine race results from the 800 metres to the marathon, paint a stark picture. Africans, eight from Kenya, hold the top 10 places. Among the women, the top three, and seven out of 10, are Kenyan. However, because of social taboos against women runners in Africa, non-Africans remain somewhat more competitive.

If you ask media "experts" what is behind this extraordinary phenomenon, be prepared for the usual cliché that "soft" white athletes cannot match gruelling African training regimens. The North American presence in distance running rests entirely on the shoulders of two Africans who emigrated to the United States: Khannouchi and Meb Keflezgihi, a native Eritrean, who crushed the American 10,000-metre record in May.

East and North Africans who share an evolutionary history have clocked more than 60% of the best times ever run in distance races. Kenyans win 40% of international events. The Nandi district in East Africa's Great Rift Valley, with only 500,000 people -- 1/12,000 of Earth's population -- wins an unfathomable 20%, marking the greatest concentration of raw athletic talent in sports history.

What's going on? Science certainly does not support the popular notion that Africans prevail because they train harder or run as kids, myths peddled by the media. "I lived right next door to school," laughs Kenyan-born Wilson Kipketer, world 800-metre record holder. "I walked, nice and slow." For every Kenyan who runs 100 miles a week, there are others, like Kipketer, who get along on 30.

The explanation for this phenomenon can be found mostly in the genes. Though individual success is about opportunity and "fire in the belly," thousands of years of evolution have left a distinct footprint on the world's athletic map.

"Very many in sports physiology would like to believe that it is training, the environment, what you eat that plays the most important role," states Bengt Saltin, director of the Copenhagen Muscle Research Centre, who outlined his findings in Scientific American. "But we argue based on the data that it is in your genes whether or not you are talented or whether you will become talented. The extent of the environment can always be discussed but it's less than 20%, 25%."

East and North Africans, runners from southern Europe, and those from regions in South Africa, Mexico and South America are born with a biomechanical package for endurance activities, the consequence of thousands of years of evolution in highland terrains: lean physiques, large lung capacity and a preponderance of slow twitch muscle fibres.

This is not an issue of black and white. East Africans have a different genetic makeup and body type than the world's top hurdlers and sprinters who trace their ancestry to West Africa -- including Canada's Donovan Bailey and Bruny Surin. Canadian geneticist Claude Bouchard, formerly of Laval University and now at Louisiana State, found that West Africans have naturally smaller lung capacity (15% less compared to whites and East Africans), a preponderance of fast twitch muscle fibres, and a more muscled physique -- a gold mine for sprinting and pure jumping.

All the training in the world is unlikely to turn a North American black into an elite marathoner or an East African into a top 100-metre runner. While the fastest Kenyan 100-metre run is 10.28 seconds, 5,000 on the all-time list, blacks who trace their ancestry to West Africa hold the top 200 and 494 of the top 500 100-metre times.

East Asians, who are not very competitive at jumping and sprinting because of naturally high levels of body fat, a squat body structure and more slow twitch fibres, are prominent in diving, skating, racquet sports and martial arts. When dexterity and flexibility are key, East Asians shine -- hence the term "Chinese splits" in gymnastics.

Whites of Eurasian ancestry, who are most likely to have strong upper bodies, will be big winners in the field events at the world championships. The few competitive white male distance runners are almost exclusively from southern Portugal, Spain and Italy, and share many of the characteristics -- and undoubtedly the genetic makeup -- of North and East Africans.

"Differences among athletes of elite calibre are so small," notes Robert Malina, Michigan State anthropologist and editor of the American Journal of Human Biology, "that physique or the ability to fire muscle fibres more efficiently that might be genetically based ... it might be very, very significant. The fraction of a second is the difference between the gold medal and fourth place."

Could a runner who is not from Africa win a world record in distance running? Certainly, for genes only circumscribe possibility (or innate capacity) and a race spins the roulette wheel of the human spirit. But evolutionary forces have ensured that the pool of elite distance runners is deepest in North and East Africa.

"Africans are naturally, genetically, more likely to have less body fat, which is a critical edge in elite running," notes Joseph Graves, Jr., an African American evolutionary biologist at Arizona State University. "Evolution has shaped body types and in part athletic possibilities. Don't expect an Eskimo to show up on an NBA court or a Watusi to win the world weightlifting championship. Differences don't necessarily correlate with skin colour, but rather with geography and climate. Genes play a major role in this."

Is this a racial issue? "Absolutely not," says Saltin. Why do we so readily accept that evolution has turned out blacks with a genetic proclivity to acquire sickle cell anemia, Jews of European heritage who fall victim to Tay-Sachs, Asians who are genetically more reactive to alcohol and whites with a vulnerability for cystic fibrosis, yet find it racist to acknowledge that East African distance runners, white power lifters and sprinters of West African ancestry are aided, in large part, by genetics?

Humans are different, a product of the inseparable relationship of genes and environment. Popular thinking, still reactive to the historical misuse of "race science," lags this new bio-cultural model of human nature. Society pays a large price for not discussing this subject openly, if carefully. Events such as the world championships provide an opportunity to broaden our understanding of the genetic revolution now unfolding. Scientists are perfecting genetic tools that could help us understand what makes humans run faster, jump higher and throw farther -- as well as save lives by finding cures for so many threatening genetically based diseases.